Jon Hendricks obituary

Jazz singer who brought the vocalese technique to global audiences with the trio Lambert, Hendricks and Ross

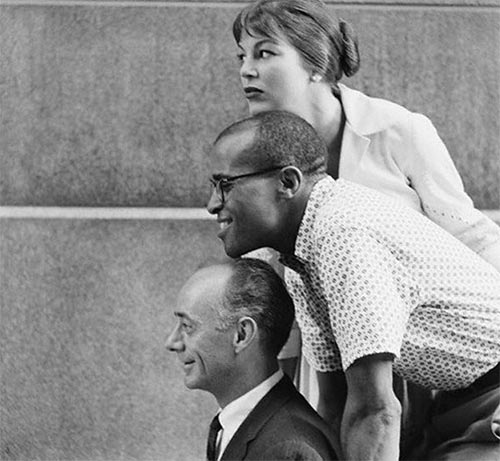

Jon Hendricks performing in 1969

When the singer Jon Hendricks declared, during a gig at the age of 80, that the next stop was 100, the likelihood of him getting there seemed almost self-evident. Back in 2002, as he bounded onstage at the Jazz Cafe, London, in a glittering gold suit, hat cocked over one eye, his yodelling, scatting, tone-bending reinvention of jazz classics by Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk or Count Basie sounded like the work of an indestructible musical force. Hendricks, who has died aged 96, was a funny, articulate and creatively intelligent master of a hard art, who took chances with vocal gymnastics and unpremeditated improv flights that few jazz singers had attempted or imagined before him, and he could mimic the sounds of instruments with uncanny fidelity.

He was a model for some of the best male singers in jazz history, including Bobby McFerrin, Al Jarreau, Mark Murphy and Kurt Elling, but Hendricks’ most lasting legacy was his expansion of the art of vocalese, the technique of fitting wittily hip lyrics to the melody lines of instrumental jazz themes and improvisations, as pioneered by the singers Eddie Jefferson and King Pleasure in the early 1950s. Some of the jazz cognoscenti disliked the style’s occasional invitation to technical tightrope-walking and showbiz bravura, but Hendricks was to give vocalese a global platform through his collaborations with Dave Lambert and Annie Ross in the vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks and Ross.

Lambert, Hendricks and Ross

Hendricks was born in Newark, Ohio, one of 15 children born to Alexander Hendricks, a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal church, and his wife, Willie Mae (nee Carrington), a choir leader. The boy first sang in public with the choir at his parents’ church, and on the family’s move to Toledo in 1935 he began singing on local radio, and working in the city’s Waiters and Bellmen’s Club with a sensational young pianist, Art Tatum, that the wider world was on the verge of discovering. After school, Tatum would give the boy informal music lessons – often playing him a dizzying improvised run and not letting him off the hook until he could flawlessly sing it back.

Hendricks worked as a singer in Detroit in the 40s, and served in the US army following the Normandy landings – a traumatising experience for reasons other than combat, since the military police took to firing on him and other black servicemen for the suspicion they had consorted with French women. They went Awol to avoid their tormenters and were imprisoned for desertion.

On his release at the war’s end, Hendricks continued to sing and play drums around Toledo, took an English literature course at the city’s university, and considered studying law. But in 1950, he met Charlie Parker at the Civic Auditorium in Toledo. His wife, Connie, asked the saxophone star if her shy young husband could sit in with him, and after their performance Parker reportedly told Hendricks to forget the law and come to New York.

In 1952, Hendricks wrote some songs in New York for the “jump-music” star Louis Jordan (Jordan’s hit I Want You to Be My Baby was a Hendricks song), but struggled to make an impact as a singer. However, when he encountered Jefferson’s lyrics for the James Moody saxophone solo on Moody’s Mood For Love, Hendricks became fascinated by the possibilities that vocalese opened up, and the following year he began exploring them with Lambert. When Lambert suggested they should apply the technique to the much-loved riff-packed hits of Count Basie, Hendricks obliged with enough new lyrics for an album, originally built around the two singers, a rhythm section, and a vocal choir mimicking the big-band horns.

But the chorus could not catch the supple magic of the Count Basie band sound, so Ross was brought in to coach it, on the strength of her own successful vocalese composition, Twisted – a witty 1952 take on psychoanalysis based on a Wardell Gray saxophone solo. But the music still did not work, until the impromptu trio of Lambert, Hendricks and Ross dispensed with the choir and performed all the vocals, with the big-ensemble feel captured by the experimental studio technique of overdubbing. “It was one of the greatest moments of my life when I heard those tapes back,” Ross told me in 1997. “I knew we had something incredible.”

Full Story